The correct test strategy depends on what you need to verify, how many boards you build, and how much design access you have. In-Circuit Test (ICT) is the fastest and most defect-focused option for high-volume production when test points are available.

Flying Probe Test (FPT) is the most flexible and cost-effective choice for prototypes and low-to-medium volumes where fixtures are impractical.

Functional Test (FCT) is the only method that validates real-world behavior and system performance, but it cannot reliably isolate manufacturing defects on its own. In practice, manufacturers often combine these methods because each catches a different class of failures.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhy PCB Test Strategy Matters in Modern Electronics

Electronics manufacturing defect rates are low by historical standards, yet the cost of a single escaped defect has increased.

According to IPC and iNEMI roadmaps, assemblies routinely exceed 1,000 components, with fine-pitch BGAs and microvias dominating new designs.

A solder bridge under a BGA, a wrong resistor value in a feedback loop, or a marginal power rail can each lead to field failures that are difficult to root cause after shipment.

Test strategy is therefore not about choosing one tool, but about placing the right verification at the right point in the production flow, balancing coverage, speed, and cost.

In-Circuit Test (ICT): Deep Electrical Visibility at Scale

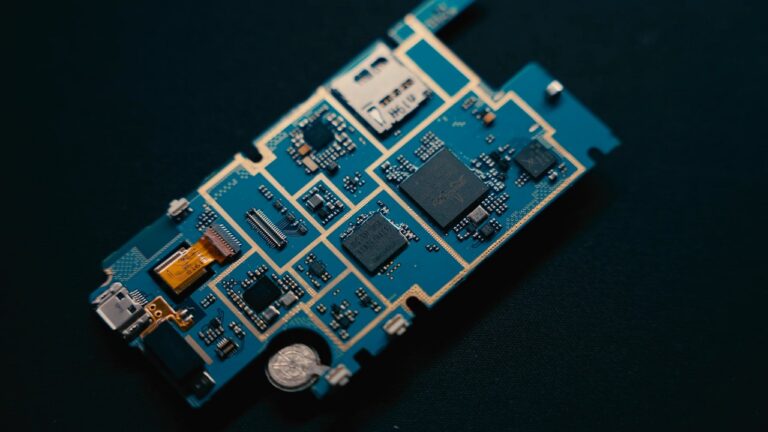

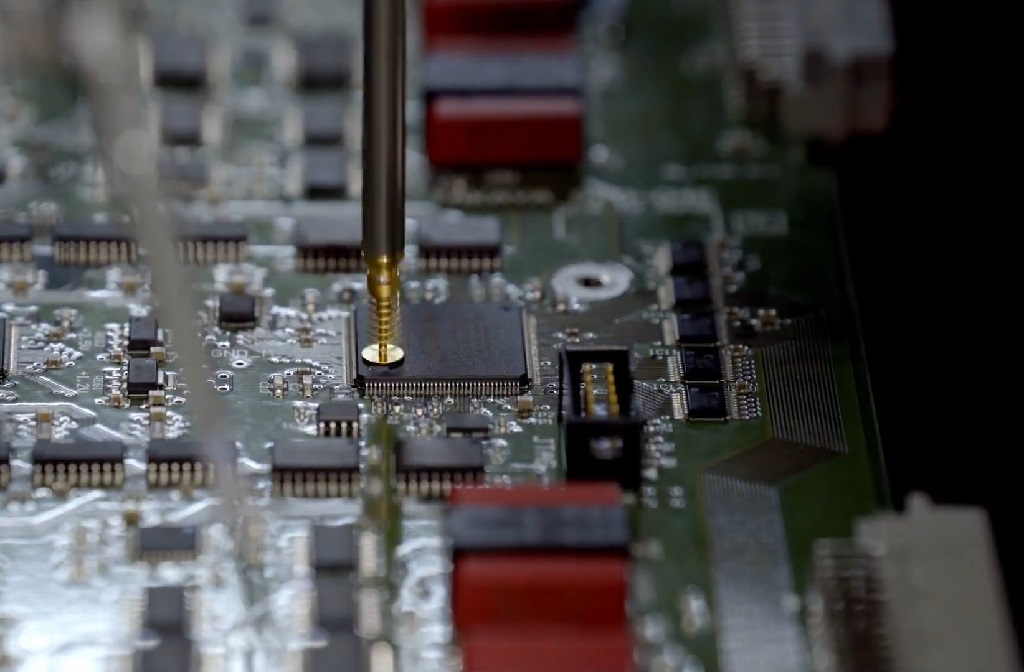

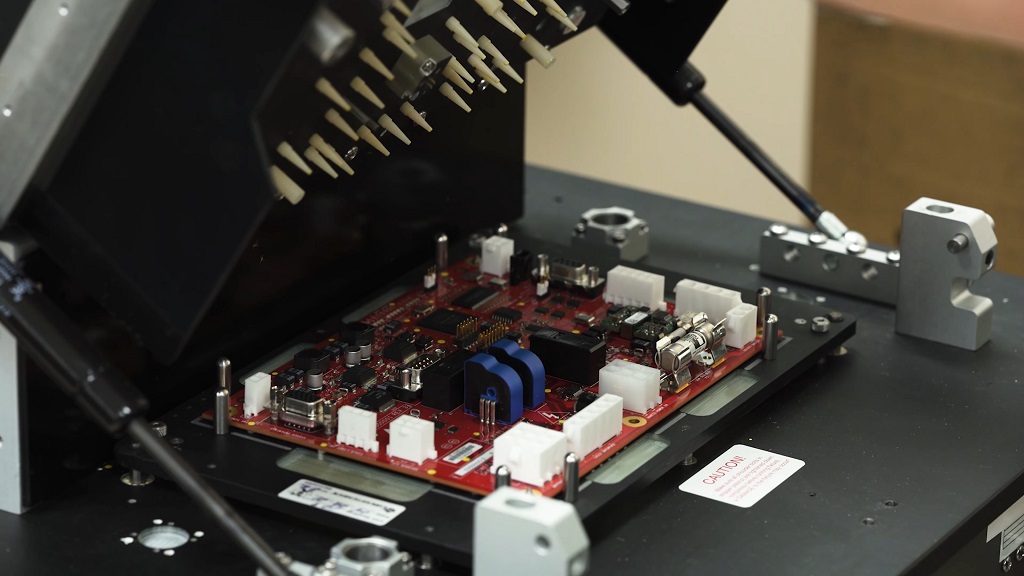

In-Circuit Test uses a bed-of-nails fixture with hundreds or thousands of spring probes that contact dedicated test pads on the PCB.

Each node is accessed individually, allowing direct measurement of resistance, capacitance, diode orientation, continuity, and shorts. ICT systems typically include powered tests for basic voltage and current checks, but their core strength is structural fault coverage rather than functional behavior.

The capital cost of ICT is driven by fixture design. A custom fixture can cost from several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars, depending on board complexity and probe count.

That cost is justified when volumes are high because test time per board is extremely short, often under 30 seconds, enabling inline testing without slowing production. Coverage can exceed 90 percent of solder and component placement defects when the board is designed for test access.

Typical faults detected by ICT

ICT excels at catching wrong component values, missing components, reversed diodes, open nets, and solder shorts. It struggles with defects hidden behind complex interactions, such as marginal timing issues, firmware problems, or analog performance under load.

ICT in a production context

ICT is common in consumer electronics, automotive PCBs, and industrial controllers where volumes justify fixtures and where regulatory or reliability requirements demand high structural coverage.

Flying Probe Test (FPT): Flexibility Without Fixtures

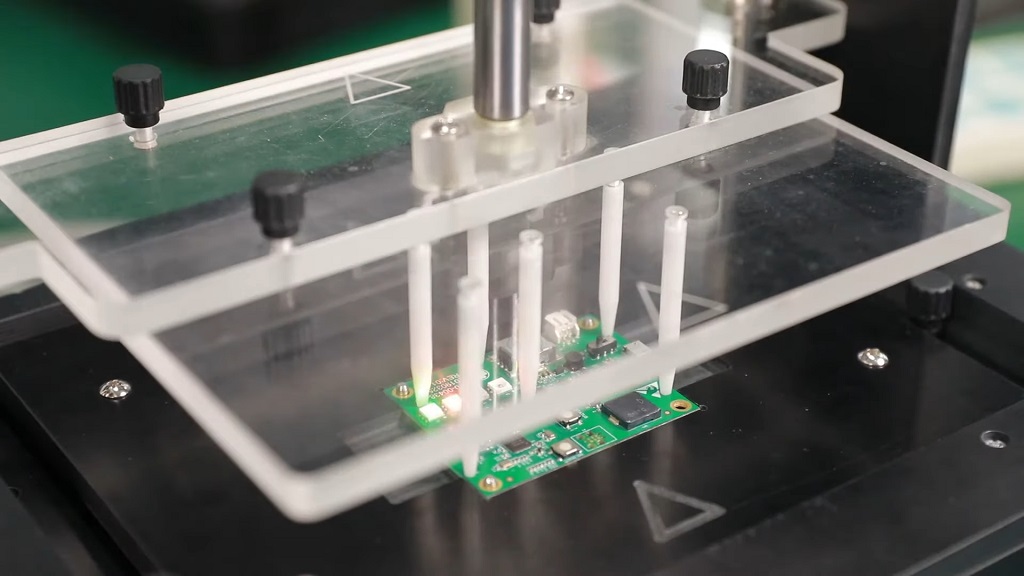

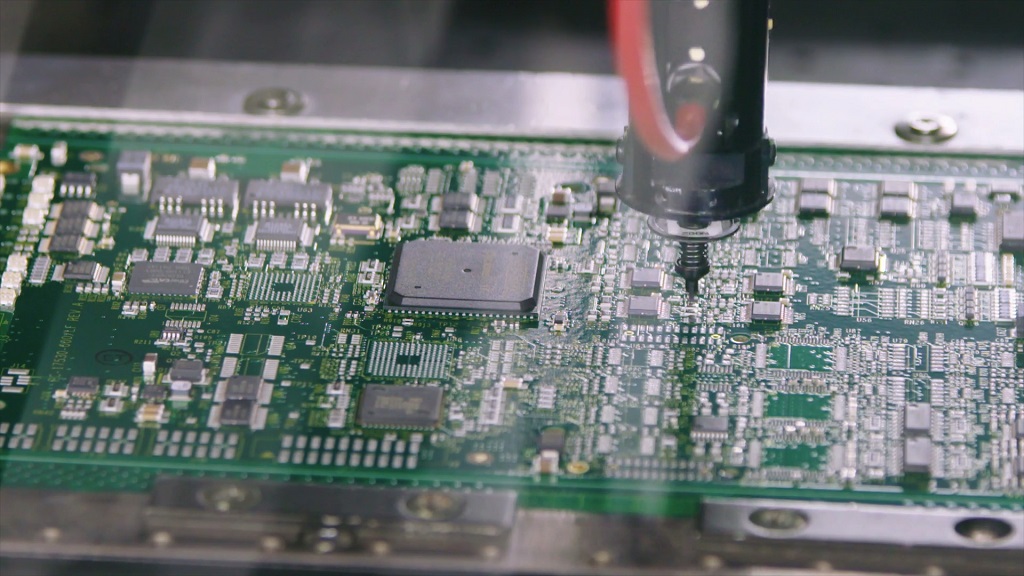

Flying Probe Test uses movable probes guided by CAD data to contact test points sequentially. Because it requires no custom fixture, the setup cost is dramatically lower, making it ideal for prototypes, engineering validation builds, and small production runs.

Modern flying probe systems use multiple probes operating in parallel, reducing test times compared to earlier generations. Even so, FPT remains slower than ICT, with test cycles ranging from several minutes to over ten minutes depending on board density and coverage goals.

What flying probe tests well

A flying probe can perform continuity checks, resistance measurements, diode tests, and limited powered tests. It can also detect opens and shorts under BGAs using capacitive sensing and boundary scan integration. However, because probes move mechanically, throughput is limited, and coverage may be reduced if test access is constrained.

Role in product lifecycle

A flying probe is often used early in a product’s life to validate manufacturability and catch layout errors before committing to expensive fixtures. Many manufacturers continue using FPT for service spares or low-volume variants long after high-volume products move to ICT.

Functional Test (FCT): Validating Real Behavior

Functional Test verifies that the assembled board performs its intended function under operating conditions. The board is powered, stimulated with real or simulated inputs, and observed for correct outputs, timing, and behavior. This can range from simple power-on checks to complex automated test sequences interacting with firmware, communications interfaces, and sensors.

Unlike ICT or FPT, Functional Test does not require direct access to every node. It treats the board as a system rather than a collection of components.

This makes it indispensable for catching defects that structural tests miss, such as incorrect firmware, configuration errors, marginal analog performance, or thermal issues under load.

Limitations of functional testing

The Functional Test is poor at fault isolation. When a board fails, determining whether the cause is a resistor value, a solder joint, or a silicon defect often requires additional diagnostic steps. Test development can also be time-consuming, especially when firmware and hardware evolve in parallel.

Where functional testing fits

Functional Test is mandatory in safety-critical, regulated, or performance-sensitive products. It is common in medical devices, industrial automation, aerospace subsystems, and network equipment.

Side-by-Side Comparison

Core characteristics

| Test Method | Primary Purpose | Fixture Required | Typical Test Time | Best Volume Range |

| ICT | Structural defect detection | Yes | Seconds | Medium to high |

| Flying Probe | Structural checks without fixtures | No | Minutes | Prototype to low |

| Functional Test | Behavioral verification | Often | Minutes | All volumes |

Defect coverage profile

| Defect Type | ICT | Flying Probe | Functional Test |

| Opens and shorts | High | High | Low |

| Wrong component value | High | Medium | Low |

| Missing or reversed parts | High | Medium | Low |

| Firmware issues | None | None | High |

| Performance under load | Low | Low | High |

| Timing and protocol errors | Low | Low | High |

Cost Considerations Across the Product Lifecycle

Cost is not only about equipment price but also about engineering time, scrap reduction, and yield improvement. ICT has a high upfront fixture cost but a low per-unit cost.

A flying probe has a minimal upfront cost but a higher per-unit cost due to longer test times. Functional Test sits somewhere in between, with cost driven by test development complexity rather than hardware.

Simplified cost model

| Cost Element | ICT | Flying Probe | Functional Test |

| Upfront investment | High | Low | Medium |

| Per-unit test cost | Low | Medium to high | Medium |

| Debug and diagnosis cost | Low | Medium | High |

| Scalability | High | Limited | Medium |

Design for Testability and Strategy Selection

The test strategy cannot be separated from PCB design. ICT requires accessible test pads and sufficient spacing. Flying probe tolerates reduced access but still benefits from thoughtful pad placement. Functional Test depends heavily on software hooks, debug interfaces, and stable power architectures.

Design teams increasingly plan for a layered strategy, using flying probe during early builds, transitioning to ICT for volume production, and retaining functional test as a final gate. This approach aligns with industry best practices promoted by IPC-9191 and automotive standards such as IATF 16949, which emphasize defect prevention and early detection.

When Combining Methods Makes Sense

No single method provides complete coverage. High-reliability manufacturers often combine ICT or flying probe with functional test to reach coverage levels above 95 percent. Structural tests catch assembly defects early, reducing time wasted on debugging functional failures, while functional tests ensure the product actually works in its real environment.

In my experience reviewing production data, the largest yield improvements come not from adding more tests, but from placing the right test at the right stage. Early structural testing reduces downstream rework costs, while final functional testing protects customers from subtle failures that only appear under real operating conditions.

Final Perspective

Choosing between Functional Test, Flying Probe, and ICT is not a matter of preference but of alignment with product volume, design maturity, and risk tolerance. ICT delivers speed and defect isolation at scale.

Flying probe delivers flexibility and low entry cost. Functional Test delivers confidence that the product does what it is supposed to do. Most robust manufacturing lines use all three, deliberately and with clear roles, because modern electronics are too complex to rely on a single view of quality.